The Freteval Forest – Operation Sherwood

Roger Stanton

In early 1944 a plan was in preparation to concentrate evaders into areas that would be safely isolated from an Allied advance, and from the expected German withdrawal. By this stage of the war all escape lines were experiencing many problems with the movement of evaders from Belgium and Northern France to the Pyrenees due to Allied aircraft targeting communications, railways and river and road bridges. The provision of food was becoming a problem in the large towns and cities, and safe-houses were being compromised. Evaders could no longer be moved easily along the lines and several ‘choke points’ were developing, identified by MI9 as needing to be cleared.

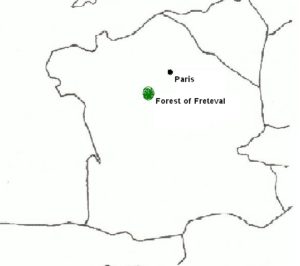

From mid 1943, MI9, working alongside MI-X, developed a plan called Operation Marathon. The plan focussed on three forested areas: near Rennes in Brittany, near Chateaudun and in the Belgian/French Ardennes. MI9 proposed that once the battle for France began all evaders at ‘choke points’ should be moved to one of the forest areas nearest to them. This would then ensure that they were not trapped behind the front lines and also ensure that they were not in the direct battle areas

The camp near Chateaudun was based on the ‘Foret de Freteval’ and known as Operation Sherwood. For many years, due to the modesty of the Loir-et-Cher and the Eure-et-Loir Resistance groups, the Comète Escape Line and of course the evaders themselves, very little was known of this extraordinary story.

152 aircrew evaders from Great Britain, America, Canada, Belgium, New Zealand and Australia lived in perfectly organised camps in the forest between May and September 1944, in the heart of occupied France, under the very noses of German troops. It is quite remarkable how the Resistance groups involved managed to keep such a large number of evaders hidden and a secret from the inhabitants of local villages. Due to the excellent organisation of the camps, not a single evader was lost or captured.

From Brussels to the Western Pyrenees, Comète was the main escape line for aircrew evaders, so it was to Comète that MI9 went for help and advice. A Belgian officer, Airman Loucien Boussa serving with the RAF, was appointed as a main organiser. He experienced a hazardous journey to the forest which began with his landing on the coast of Spain, followed by a crossing of the Pyrenees, a meeting up with Comète ‘officials’ in the Basque country at St Jean de Luz and after that he headed north to Paris. Travelling with Boussa was radio operator Francois Toussaint. They reached Paris on the 13 May 1944. Boussa immediately contacted Comète and recruited Baron Jean de Blomaert into the plan. Blomaert was a remarkable man who, considering that the average ‘life-span’ of a helper on an escape line was approximately 90 days before capture, had worked with the Comète Line since 1940. He had many aliases and was known to the Germans as ‘The Fox’.

On receiving an urgent message from London “Invasion near, hide evaders on site”, Boussa ordered an immediate meeting with the leaders of Comète, the head of the FFI of Eure-et-Loir Maurice Clavell (Sinclair), Andre Gagon (later Mayor of Chartres) and two members of the Liberation Movement Pierre Poitevan (Bichat) and R Dufour (Duvivier). Bichat and Duvivier insisted that the Resistance Leader of the ‘Libe Nord’ for the region of Chateaudun, Omer Jubalt, should also be involved. Jubalt, a former gendarme, later to become head of all Resistance groups in the Freteval area, had ‘gone to ground’ with a Resistance colleague, Robert Hakspille (Raoul), having been warned of impending arrest by the Gestapo for Resistance activities.

However, Jubalt and Hakspill who, who were still paid by the gendarmerie, started work immediately on their designated job of organising the countryside. Working from safe-houses and from the forest, they enjoyed the respect and support of the local people who ‘watched out’ for them. Water sources were located, arms dumps plotted, safe-houses arranged, couriers and organisers appointed. Farmers, millers, doctors and bakers were all recruited from loyal Frenchmen. For security reasons the radio operator was moved ten miles away to the town of Moulineauf. Mme Jubalt ran a safe-house and the Jubalt’s young daughters, although still at school, became couriers for airmen.

It is difficult to imagine what life in France was like in 1944. Everything was rationed to insufficient quantities. To obtain food, clothes and shoes was virtually impossible. In addition there was no fuel or petrol for cooking, heating or driving.

The farm at Bellande, ran by the Fouchard family, was chosen as a food warehouse for the camp and as a slaughterhouse for animals. In early spring Jubalt and Boussa met M and Mme Fouchard and their daughters Micheline, Simone, & Jacqueline. They collected tarpaulins, sheeting and other materials and together with five aircrew from safe-houses, started to set up the camp.

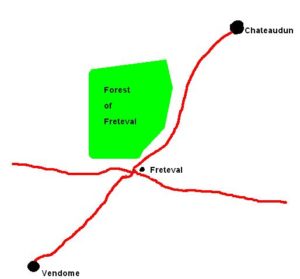

The first aircrew arrived. Evaders were usually collected from the station at Chateaudun and walked to the forest at night. Horse drawn carts and cycles were also used and the evaders arriving by cart, were provided with pitchforks to give the impression they were farm labourers. A guard post was positioned about 1km from the camp to interrogate all evaders on arrival. Other evaders already sheltering in safe-houses in the area tensely awaited relocation to the forest as,

regrettably, the previous February, ten people from nearby Vendome had been arrested for hiding aircrew. The helpers had been roughly interrogated but gave nothing away; their fate was then to be deported to a concentration camp.

The organisation of the camp was amazing. Local farmers delivered live animals, and local bakers provided bread. Micheline Fouchard delivered food and animals daily using her horse and cart. On one occasion she was nearly killed when strafed by Allied aircraft. A roster for night fishing, guard duty, cooking and lookouts was arranged. A head cook was appointed. All tentage was covered in foliage, which had to be changed every few days. A parachute drop provided the camp organisers with French money, medical supplies and cigarettes. The Resistance patrolled the outer perimeter of the forest. The key to morale was information, so a bulletin board was placed in the centre of the camp. No one was allowed into the forest, with the exceptions of the doctor and the local barber, Albert Barillet from Cloyes, who paid a weekly visit.

A field hospital was set up away from the main camp. The badly injured, mostly burns victims, were cared for in the homes of local people, who were mainly members of the Resistance. Mme Dupres of Villeboute, who was an English speaker, turned her home into a small hospital with the assistance of a lady companion and throughout the period of the camp until liberation, never had less than five injured airmen in her home. The couriers for airmen, between the camp and Mme Dupres’ home, were the schoolchildren Ginnette and Jean Jubault.

Incidents did occur:

While riding a bike about 100m in front of a horse and cart transporting evaders, Virginia d’Albert Lake was stopped by German soldiers at an impromptu roadblock. Betrayed by her American accent, Virginia was arrested and after harsh treatment sent to Ravensbruck where she nearly died. The evaders involved in the incident saw the soldiers and fled. Their guide, Daniel Cogneau, had to recover the cart and later search for his evaders. Virginia never betrayed the camp or the Resistance.

In July, Maxine Plateau, a member of the Eure et Loire Resistance who supplied most of the food for the camp, was also arrested after a parachute drop of arms was located on his land. He was severely tortured but revealed nothing. Security at the camp was increased.

Mme Hallouin, who lived nearby and was able to view approaches to the forest, kept a wood fire burning in her home together with a supply of leaves to signal a warning of the approach of any Germans. The profuse smoke emanating from the leaves would alert the camp sentries and the camp could be vacated.

IS9 were in the process of making preparations to liberate the Forest of Freteval under the Operation Sherwood plan. On arrival at Le Mans on the 10th August the Battle Group stopped and Airey Neave set up IS9 headquarters in the Hotel Moderne. Now about 50 miles from Freteval, he toured the various US HQs to try to request men and transport to help liberate the camp. Despite his efforts, the Americans had other priorities on the battlefield and declined to help, stating that light tanks and infantry would be a necessary requirement as German tanks and troops were known to be in the area.

A disappointed Neave returned to Le Mans and sent out a section to seek out the local French Resistance to request transport for the rescue using civilian vehicles. Meanwhile he became aware that a ‘rather tough looking group’, who turned out to be a British 2SAS Squadron under Captain Anthony Greville–Bell, and who had completed their operation, were resting in Le Mans awaiting orders from London and were now also resident in the Hotel Moderne, having parked all their heavily armed jeeps in the courtyard. That evening another Squadron comprising Belgians from 5SAS arrived, together with their own radios. Greville-Bell contacted London and the next day received confirmation that both SAS Squadrons could liberate Freteval with Neave.

Maps were studied, routes chosen and, as it was not known who controlled the roads, it was decided that Capt. Peter Baker should lead a recce and also explain to the men in the forest that they had to wait for organised liberation and not disperse. His team, comprising five SAS troops and their officer, left in jeeps, acquiring a motorbike along the way, and arrived in the early evening having been engaged in a fire-fight en route, in which one man was injured.

The next morning the Americans were again approached for vehicles, and again refused. However, later that day, Neave was requested to head to the main square in Le Mans where he was met by members of the Resistance who had gathered sixteen coaches and trucks for the camp liberation. They all left at speed the next morning, the SAS leading the way and covering the rear.

Passing through flag waving villages and towns en route, the party were delayed by welcome speeches and champagne. They finally arrived at the camp and, by afternoon, were back in Le Mans. The roll call of the camp numbered 152; 132 were collected by Neave’s party and another ten by American troops who were in the area. It was assumed that the remainder had left or headed for the villages. On the 14th August Baker volunteered to return to the forest camp with the SAS to try to find the missing airmen (only to discover that they too had left with the Americans) and was caught up in a fire fight with the French Resistance – who thought they were Germans! No one was hurt.

It is remarkable that MI9, together with Comète and local Resistance groups under the command of Omer Jubault, had managed to lead 152 Allied evaders, mainly at night, into the Freteval Forest, then hidden, protected, clothed, nursed and fed them within land and air sight of German patrols. It is remarkable too, that the operation took place over a period of four months within 100m of a road used by many German vehicles.

Today on the site of the western lookout is a memorial to the Freteval story. The memorial is a stone tail fin of a Lancaster Bomber dedicated to the 152 evaders and the bravery of the French people who hid them. The success of the whole project indicates that none of the local people who were arrested by the Germans gave anything away despite torture or harsh treatment in the concentration camps.

Finally, the cost to local people:

Mesdames Lucienne (Callu) Proux and Marie-Louise (Delbert) Caspard, Messieurs Robert Germond, Rene Roussineau, Raymond Evrard and Maurice Pomier did not return from concentration camps.

Madame Helen Germond , Virginia d’Albert Lake (Jacqueline), Messieurs Lucien Proux, Paul Taillard and Raymond Cordier all returned from concentration camps.

Thanks must go to Cecile Jubault and Daniel Cognac who supplied much of the information about the Freteval Forest Camp, near Villeboute, during my visits to the area in May 92, and May 94 – Rog Stanton.